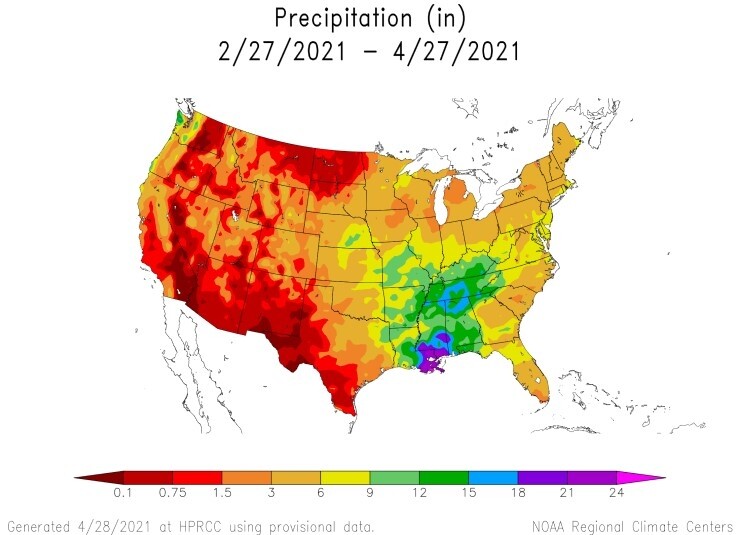

Map showing precipitation in inches for the last 60 days over the continental U.S.

(Image credit – High Plains Regional Climate Center)

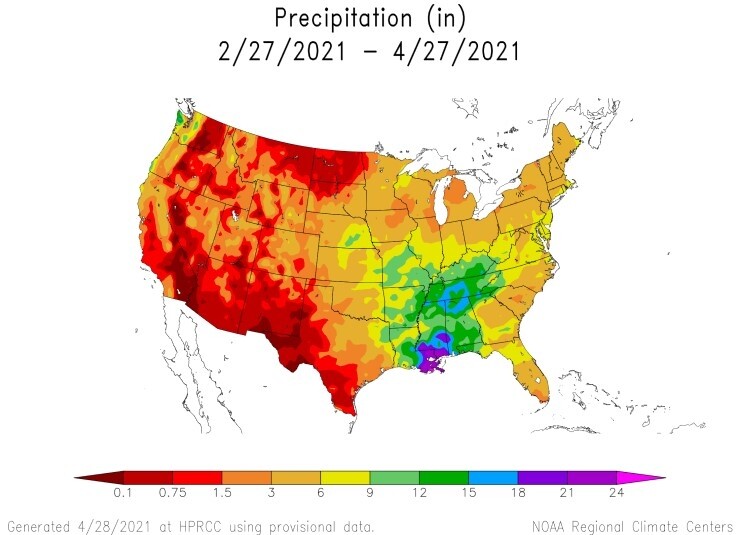

Map showing precipitation in inches for the last 60 days over the continental U.S.

(Image credit – High Plains Regional Climate Center)

A longstanding concept for centralizing the dissemination of climate-related risk information is seeing renewed attention from lawmakers as President Biden pushes to vastly expand federal climate research and mitigation initiatives.

Last week, the House Science Committee held a hearing

Republicans at the hearing revived arguments that such an effort would risk duplicating existing activities.

Environment Subcommittee Chair Mikie Sherrill (D-NJ) opened the hearing by noting

“While the private sector is a critical partner, it cannot replace an authoritative, accessible baseline of federal science and climate services,” she remarked.

Sherrill also highlighted two new bills she has introduced, the PRECIP Act

Committee Chair Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) did not attend the hearing but in a written statement

Committee Ranking Member Frank Lucas (R-OK) warned against

Environment Subcommittee Ranking Member Stephanie Bice (R-OK) similarly argued Congress should “focus on what information and data localities need, not just increasing bureaucracy with another government agency or service.” She added, “Through federal-led partnerships with academics, states, private industry, we can identify what information is most needed and then work to provide it in a cost-effective, resourceful way.”

Among the witnesses testifying at the hearing was climate scientist Richard Moss, who directed the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) during the presidencies of George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Citing his experience working with state agencies seeking climate information, Moss observed that “there is a lot of confusion among users about where to turn.”

He advocated for developing a “more unified federal effort that doesn’t replace or try to set up a single source for all information, but that serves as a point of contact and helps direct people to the appropriate information.” However, he said that the research community currently does not have enough resources to “do the kind of customization that we need to make the data relevant at local levels.”

“You can get data on temperature, precipitation, but what does it actually mean for how you might have to change your cropping cycles? Or where things are beginning to flood?” he said.

Rep. Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR) noted that Democrats on the House Climate Crisis Committee have proposed

Moss replied, “I think you will have to act to establish some kind of a new authority that has sufficient resources and clout to work better across the agencies,” noting that USGCRP is not focused on operationalizing the research it produces. “USGCRP agencies feel that they’re research agencies, and so I think that we really need much more on the operations side in order to do this kind of locally relevant synthesis and application,” he explained.

Another witness, Beth Gibbons, executive director of the American Society of Adaptation Professionals, similarly argued for developing new means of conveying climate information beyond the NCA report.

“It’s not just enough to have a well-researched report and then put it on the shelf and hope somebody comes and finds it to read. We need to have developed reports that are based on the priorities that exist in communities, and then bring climate information into those priorities in a way that becomes meaningful for them and engages the communities, from the research, to the release, to the implementation of action that follows,” she said.

NOAA first formally proposed creating a National Climate Service at the end of the George W. Bush administration, when the head of the agency, Conrad Lautenbacher, advanced

President Biden’s newly announced

“The diversity of products and services is apt to be broader for an NCS,” he said.

Meanwhile, in 2007, then-Sen. John Kerry (D-MA), who is now leading President Biden’s international negotiations on climate, introduced legislation

The climate service concept gained momentum at the outset of the Obama administration with the support of the House Science Committee, which advanced a bill

Subsequently, in 2011 NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco proposed

Now, though, the climate service idea has returned in certain corners of Congress after lying dormant for the past decade. For instance, outside the House Science Committee, the top Republican appropriator for NOAA, Rep. Robert Aderholt (R-AL), asked specifically

Lubchenco, who is now leading OSTP’s climate and environment portfolio, said she is “delighted” in the renewed congressional interest in the subject, responding to an audience question at the American Meteorological Society’s Washington Forum

“I think that there will be ample opportunity for us to consider the best ways to deliver the kind of integrated services that are needed across the agencies,” she added.