New Astronomy Bachelors and Masters: What Comes Next

Earning a bachelor’s or master’s degree in astronomy opens a variety of career path choices. Post-degree outcomes for astronomy bachelor’s degree holders are wide ranging. Astronomy bachelors have the potential to continue studies at the graduate level in astronomy or another discipline, the option of looking for employment, continuing in employment they already have, or possibly taking some time off. In addition to sorting through multiple possibilities, about one-third of astronomy bachelors in the class of 2020 reported that their plans had changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This report also examines outcomes for students who earn an astronomy master’s and then leave their current institution. These master’s graduates often begin study at another institution or take employment either at a four-year college or university, or in the private sector. Using data from surveys of astronomy graduates in the classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020, we look at the range of initial outcomes for astronomy bachelors and masters. The results are intended to help faculty members and students be cognizant of the breadth of possibilities available to astronomy degree recipients. A separate report

Astronomy Bachelors

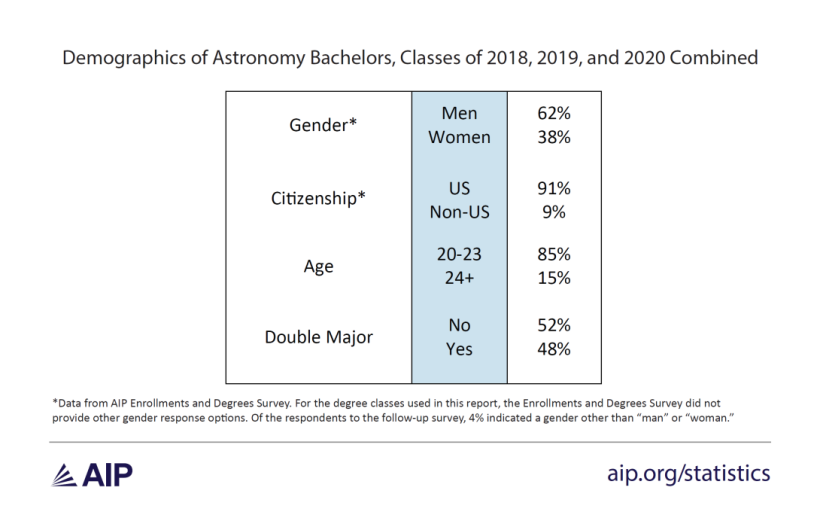

The number of students earning undergraduate astronomy degrees in the US has been steadily increasing, rising over 300% from two decades ago. In 2020 over 800 students earned bachelor’s degrees in astronomy, compared to about 600 in 2018. Women comprised over a third of all astronomy bachelors conferred in the classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 combined (Table 1). About one in seven (15%) bachelor’s degrees were granted to people over the age of 24. Just over half of astronomy bachelors indicated that they graduated with a double major, with more than three-quarters of these indicating that they were also majoring in physics.

Table 1

Choosing which immediate post-degree career path to follow can be a difficult decision. About two-thirds of astronomy bachelors indicated that a faculty member provided them with career guidance. Many circumstances can influence a new graduate’s immediate post-degree endeavors. For the class of 2020, almost a third (32%) of respondents indicated that their post-degree plans had changed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ultimately, a similar proportion of astronomy bachelors in the classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 were in the workforce as were enrolled in a graduate program in the year after receiving their degrees (Figure 1).

Graduate School

Of the nearly half of astronomy bachelors who indicated that they had enrolled in a graduate program, about three-quarters were pursuing degrees in either astronomy, astrophysics, or physics. The remaining quarter of the new bachelors who enrolled in a graduate program studied a variety of subjects, the most common being education, computer science, and earth science. Regardless of the subject, the majority (58%) of astronomy bachelors who were enrolled in graduate programs indicated they were supported by a teaching or research assistantship. An additional 20% were supported by some form of fellowship. We asked the class of 2020 whether the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their assistantship stipend or the financial aid they received; only 1% indicated that it had. As has been true in the past, a larger proportion of women (57%) were enrolled in a graduate program than men (40%).

Figure 1

Employment

Of the nearly half of the astronomy bachelors who were employed in the winter following their graduation, 10% indicated they were continuing in a position that they had held for at least six months prior to graduating. About one-third of the astronomy bachelors who entered the workforce (35%) indicated they were planning on enrolling in graduate school in the future, with most hoping to enroll in an astronomy or physics program in the following academic year. Seven percent of the new astronomy bachelors from the classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 (combined) indicated they were unemployed and seeking employment [1] in the winter following their graduation.

Employment Sectors and Salaries

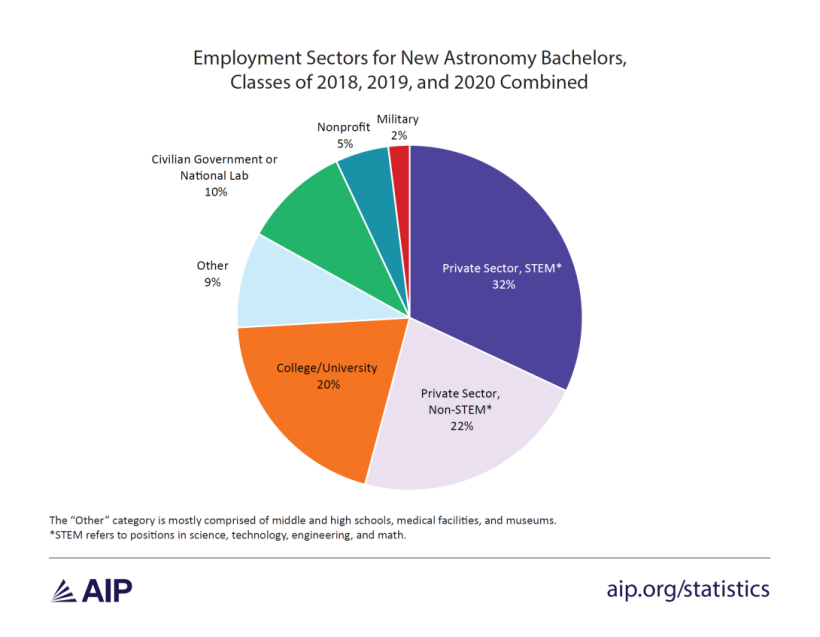

The skills and knowledge astronomy bachelors obtain while pursuing their degrees enable them to secure employment with a diverse set of employers (Figure 2). Over half of employed astronomy bachelors worked in the private sector, and most of these were working in a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) field. Colleges and universities were the next largest sector employing new astronomy bachelors, followed by civilian government positions.

Figure 2

Private Sector Employment

All respondents in STEM private sector positions indicated that they were called upon to solve technical problems at least “monthly” on a scale that also included “daily,” “weekly,” and “rarely or never.” The most common job titles for astronomy bachelors holding private sector STEM positions included “analyst,” “engineer,” and “software developer.”

Astronomy bachelors in private sector non-STEM positions held a more diverse set of positions, ranging from retail-related positions to more technical positions such as those in finance and operations. About half of the bachelors in non-STEM positions indicated that they were called upon at least monthly to solve technical problems.

Those employed in STEM private sector positions indicated higher levels of satisfaction than those in non-STEM private sector positions on measures of job security (90% vs. 69%), salary and benefits (82% vs. 29%), and overall satisfaction (86% vs. 40%). These differences are statistically significant.

College and University Employment

A fifth of employed astronomy bachelors were working at colleges or universities, with about half of these employed at the same institution from which they received their bachelors. About two-thirds of the positions in colleges and universities were in the field of physics or astronomy. The bachelors in these academic positions often had job titles such as “lab assistant” or “research assistant.” Many new astronomy bachelors in these positions considered their employment to be temporary, with 57% indicating they were planning to enroll in graduate school in the future.

Starting Salaries

Due to low numbers of reported salaries, we are able to reliably report starting salary data only for astronomy bachelors employed at colleges or universities or in private sector STEM positions. As seen in Figure 3, the median starting salary for astronomy bachelors working in private sector STEM positions is notably higher than for those at colleges or universities ($71,000 vs $38,000.)

Figure 3

COVID-19 Impacts

Toward the end of the most recent academic year included in this report, 2019-20, the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly affecting US colleges and universities. At that time, many students were sent home to remotely complete the second half of the spring semester. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected the academic lives of seniors wrapping up their final semester of college. We included a set of questions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on our follow-up survey of the class of 2020 astronomy bachelors.

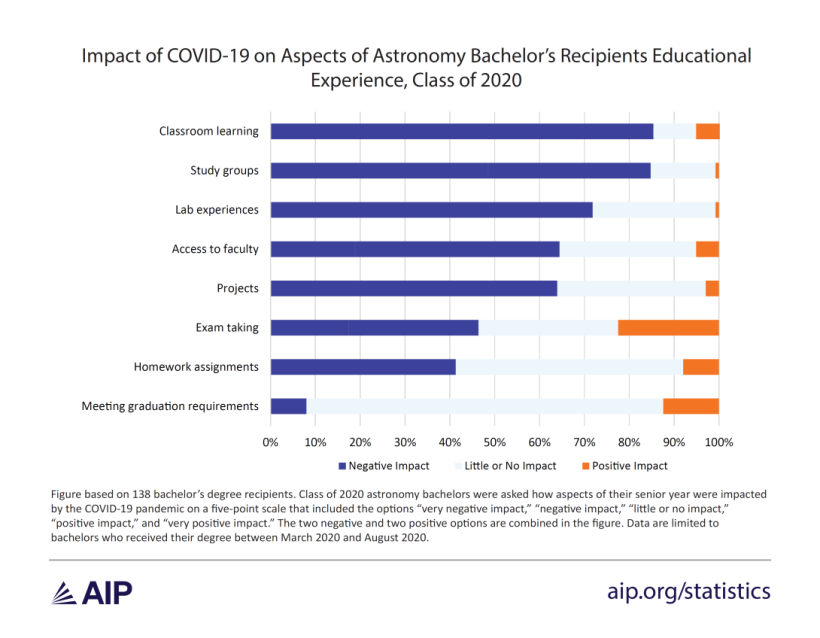

Figure 4 presents how the class of 2020 astronomy bachelors felt impacted by the pandemic’s disruptions. The three most common areas where respondents noted a negative impact on their education were classroom learning (85%), study groups (85%), and lab experiences (72%). Although 46% of bachelors felt that exam taking was negatively impacted, 22% indicated that exam taking was positively impacted, which is almost twice as many as the next highest positive impact. Of the educational experiences we asked about, “Meeting graduation requirements” showed the least amount of disruption, with 80% indicating that the pandemic had little or no impact on our respondents’ ability to meet graduation requirements. The proportion of seniors who were unable to meet graduation requirements could be higher than our results show because the data are reported only by seniors who successfully completed their degrees by the end of the spring 2020 semester.

Figure 4

Astronomy Masters

The discussion of initial outcomes for astronomy masters is complicated by the fact that not every astronomy master’s degree is the same. Some students receive a master’s degree and continue with graduate studies at the same institution. Others receive a master’s degree in astronomy or astrophysics and do not continue with graduate studies at that same department. We call this second group of students exiting masters. The rest of this discussion examines the responses from these exiting masters.

The number of students receiving an exiting master’s degree in astronomy each year is relatively small. The astronomy classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 averaged 24 exiting master’s recipients per year. We heard from 36 exiting masters (51%) from the three classes combined. Women earned about a third (32%) of exiting master’s degrees in astronomy (Table 2). Even with a relatively high response rate, the low number of exiting masters limits the level of specificity of the post-degree outcome data we can report.

Table 2

About an equal proportion of the new exiting masters in astronomy were either working or continuing with their graduate studies at a different institution in the winter following the receipt of their master’s degrees. All who continued their graduate education were enrolled in an astronomy or astrophysics program. The employed exiting masters were fairly evenly split between working at a four-year college or university and working in the private sector. Virtually all were employed in a STEM field, with the most common field being physics or astronomy. Two respondents indicated that they were seeking employment.

Conclusion

The initial post-degree outcomes for astronomy bachelors and exiting astronomy masters are similar, with an almost equal proportion continuing their education at the graduate level as entering the workforce. Most of those continuing their education are enrolled in astronomy, astrophysics, or physics programs. Most of those who go to work find jobs in the private sector.

We asked the bachelor’s class of 2020 about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their education. Many respondents reported negative impacts on classroom learning, study groups, and lab experiences. About one-third reported that the pandemic had changed their postgraduation plans. Because AIP collects initial employment data every year from physics and astronomy graduates, we will continue to report on any changes in educational experiences or employment outcomes.

Survey Methodology

Each fall the Statistical Research Center conducts a Survey of Enrollments and Degrees, which asks all degree-granting physics and astronomy departments in the US to provide information concerning the number of students they have enrolled and counts of recent degree recipients. At the same time, we ask for the names and contact information for recent degree recipients. This degree recipient information is used to conduct our follow-up survey in the winter following the academic year in which respondents received their degrees. The post-degree outcome data in this Focus On come from that survey.

Recent degree recipients can be difficult to reach because they tend to relocate after receiving their degrees. Departments often do not provide or do not have accurate contact information for their alumni. To assist us in determining outcome information and to help obtain updated contact information, we contact the advisors of nonresponding degree recipients. The information obtained from the advisors is limited to citizenship, gender, employment status, sector of employment, location (in or out of the US), and subfield of dissertation for the PhDs.

Because astronomy degree classes at all levels are relatively small, we aggregated follow-up survey response data for three classes in order to reliably report on degree recipient outcomes. The follow-up surveys for astronomy degree recipients in the classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 were administered in a web-based format. Nonresponding degree recipients were contacted up to six times with invitations to participate in the survey.

The astronomy bachelor’s classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020consisted of 596, 666, and 824 bachelors, respectively. We received post-degree information on 29% of these degree recipients. Most of the post-degree data came from the bachelors themselves, with 19% coming from advisors. Three percent of astronomy bachelors for whom we had outcome data did not remain in the US after receiving their degrees; these recipients are not included in the analyses. The class of 2020 survey included questions concerning the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the degree recipients’ post-degree plans and outcomes. The discussion on the pandemic’s impact is limited due to the low number of respondents included from that single degree cohort.

The exiting astronomy master’s classes of 2018, 2019, and 2020 consisted of 18, 28, and 25 masters, respectively. We received post-degree information on 51% of these degree recipients. Fifty percent of the post-degree data came from advisors, with the remainder coming from the masters themselves. Three percent (one respondent) of astronomy masters for whom we had outcome data did not remain in the US after receiving their degrees and are not included in the analyses.

We thank the many astronomy departments, degree recipients, and faculty advisors who have made this publication possible.

References

[1] According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the combined unemployment rate for 20-24 year-old new college graduates from the same three degree classes was 11%. See Table 3 in each of the following “Economic News Release” documents. (back)

- 2018: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/hsgec_04252019.htm

- 2019: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/hsgec_04282020.htm

- 2020: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/hsgec_04272021.htm

e-Updates

You can sign up to receive email alerts that notify you when we post a new report. Visit https://www.aip.org/subscribe-statistics-e-updates

Follow Us on Twitter

The Statistical Research Center is your source for data on education and employment in physics, astronomy, and other physical sciences. Follow us at @AIP_Stats.